The Patron Saint of Perfect Symbolism: Epstein's Interior Decorator Had the Subtlety of a Sledgehammer

When Your Entryway Art Doubles as a Confession

Jeffrey Epstein commissioned a nine-foot reproduction of The Massacre of the Innocents for his New Mexico ranch. Let that marinate for a moment. A convicted sex trafficker of minors paid two thousand dollars—chump change from his billions—for a wall-sized canvas depicting King Herod's systematic slaughter of infant boys, and hung it in his fucking entryway.

The painting, originally executed in 1591 by Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem, shows naked children being ripped from their mothers' arms and butchered. Epstein's assistant described it with admirable understatement as "the large 9'x9' canvas where they are killing babies." This is what art historians call "thematic resonance" and what the rest of us call "a psychopath leaving Post-it notes for the FBI."

The Art World's Magnificent Blindness

Here's where it gets rich: nobody in the constellation of dealers, advisors, conservators, and shippers who facilitated this transaction thought to maybe—just maybe—ask a follow-up question. Not one person in the entire supply chain from canvas stretcher to FedEx driver said, "Hey boss, the guy who wants the baby-killing painting for his sex trafficking ranch—should we perhaps alert someone?"

But why would they? Epstein had impeccable credentials in the art world. He advised Leon Black on his $2.7 billion collection. He moved in circles with Jeff Koons, Jack Lang (France's former culture minister), and collectors like Steve Tisch and Jean Pigozzi. He donated $30,000 to the New York Academy of Art for scholarships and got weird commissioned portraits in return. The art world didn't fail to see the red flags—it actively profited from color-blindness.

The Semiotics of Sociopathy

There's a school of thought that says we shouldn't read too much into people's aesthetic choices. Perhaps Epstein just appreciated Dutch Golden Age compositional techniques. Perhaps he found van Haarlem's use of chiaroscuro compelling. Perhaps he was a student of biblical iconography and Counter-Reformation theology.

Or—and hear me out here—perhaps when a sex criminal commissions a massive painting of child murder and hangs it where his victims enter his property, he's engaging in what psychologists call "power display" and what the rest of us call "being a sadistic fuck."

The painting wasn't hidden in a vault or stored in climate-controlled darkness. It was displayed. Prominently. In the entrance. Where visitors—many of them young women brought to the ranch under false pretenses—would see it immediately upon arrival. This wasn't art appreciation. It was psychological warfare disguised as interior design.

The Institutional Amnesia Industry

The newly released Epstein files reveal an entire shadow economy of art deals, loans, and LLCs designed to move masterpieces while keeping the money opaque. Epstein didn't just collect art; he weaponized the art market's fundamental feature: its commitment to discretion as a cover for its commitment to not giving a shit where the money comes from.

Galleries that would screen a middle-class buyer for proof of funds somehow never asked Epstein how a "financial advisor" and "science philanthropist" (his preferred euphemisms) generated wealth. Museums that would write thirty-page essays deconstructing an artist's relationship to power structures somehow never deconstructed their relationships to donors whose power structures included private islands and blackmail operations.

And now, post-mortem, we get the slow drip of revelations: the janky commissioned work showing up at auction, the artist who denounced him twenty years ago (and was ignored), the baroque network of shell companies and sweetheart deals that kept the whole ecosystem humming.

The Metaphor Made Flesh Made Canvas

What makes Epstein's Massacre commission so perfect is its absolute refusal of ambiguity. This wasn't a Rothko that could mean anything. This wasn't abstract expressionism open to interpretation. This was a nine-foot literalization of his crimes, executed in oil paint, commissioned for two grand, and hung with the pride of a man who knew the system would protect him.

And it did. Right up until it didn't.

The art world wants to memory-hole its Epstein years, to treat him as an aberration rather than a logical conclusion of a market that treats ethics as an externality and discretion as the highest virtue. But every now and then, the files reveal something so on-the-nose that even the most practiced institutional amnesia can't quite absorb it.

A man who massacred innocence commissioned The Massacre of the Innocents. The art world shipped it, hung it, insured it, and never asked a single uncomfortable question.

Because that's not what dealers do. Dealers deal. And business, as they say in the catalogues, was very good.

Epilogue: What Hangs in the Entryway Now

The Zorro Ranch has been sold. The painting's current location is unknown—likely in some storage facility, too toxic to display, too valuable to destroy, waiting for enough time to pass that it can be quietly auctioned as "from an important private collection."

Because that's the thing about the art world: everything eventually gets laundered. Even baby-killing paintings commissioned by dead pedophiles.

It just takes a few decades and a sufficiently vague provenance description.

The market, after all, has no memory. Only inventory.

The Oracle Also Sees...

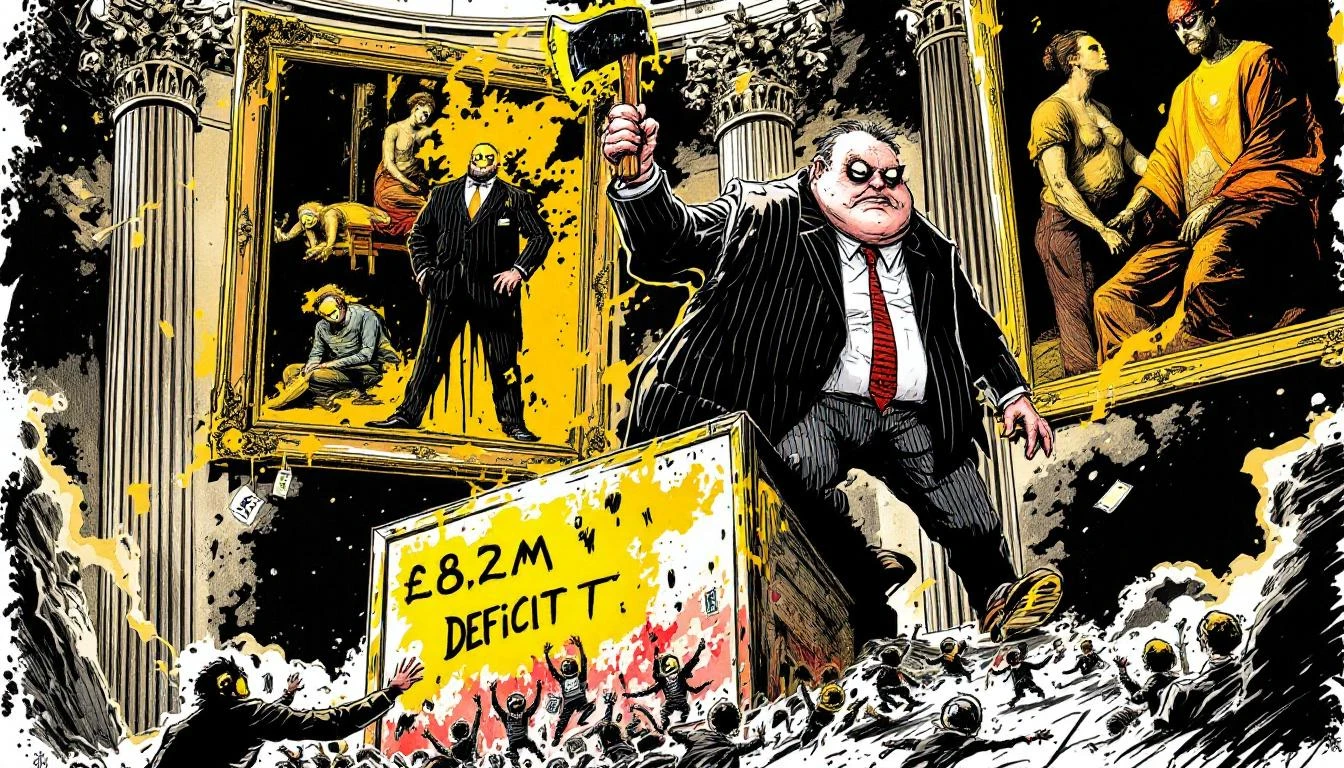

The National Gallery's Strategic Reset: Firing the Help While Sitting on £30 Billion in Wall Candy

London's National Gallery, sitting on £30 billion in masterpieces, solves its £8.2 million deficit by firing the humans who actually make the museum function. Corporate euphemism meets cultural vandalism.

The National Gallery Discovers That Priceless Masterpieces Cannot, In Fact, Pay Rent

London's National Gallery, custodian of £8 billion in masterpieces, claims it cannot afford staff while executives deploy "strategic reset" euphemisms to mask institutional moral bankruptcy.

The Long Goodbye: How Jack Lang Discovered His Epstein Problem Only After Everyone Else Did

At 86, Jack Lang discovers consequences exist. The French cultural icon resigns from Institut du Monde Arabe after his Epstein ties surface—proving that selective blindness is the art world's most perfected skill.