The National Gallery's Strategic Reset: Firing the Help While Sitting on £30 Billion in Wall Candy

When Priceless Means Worthless

The National Gallery in London — custodian of da Vincis, Turners, and Van Goghs worth an estimated £30 billion — has announced it can no longer afford the £40,000-a-year humans who actually dust the Caravaggios and prevent tourists from taking selfies with their flash on. The institution faces an £8.2 million deficit by 2027, which in the grotesque mathematics of cultural institutions means firing the docents while the directors continue drawing salaries that could fund a small Renaissance.

The phrase deployed is "strategic reset," a term of such exquisite corporate cowardice it could only have been birthed in a consultant's PowerPoint deck. What it means in non-euphemistic English: we fucked up the budget, so you're fired. The voluntary exit scheme — voluntary in the sense that a man jumping from a burning building is voluntarily choosing to fly — will save perhaps £3 million. Meanwhile, the gift shop continues hawking £45 tote bags printed with Monet's water lilies to tourists who just paid £20 to stand in a room.

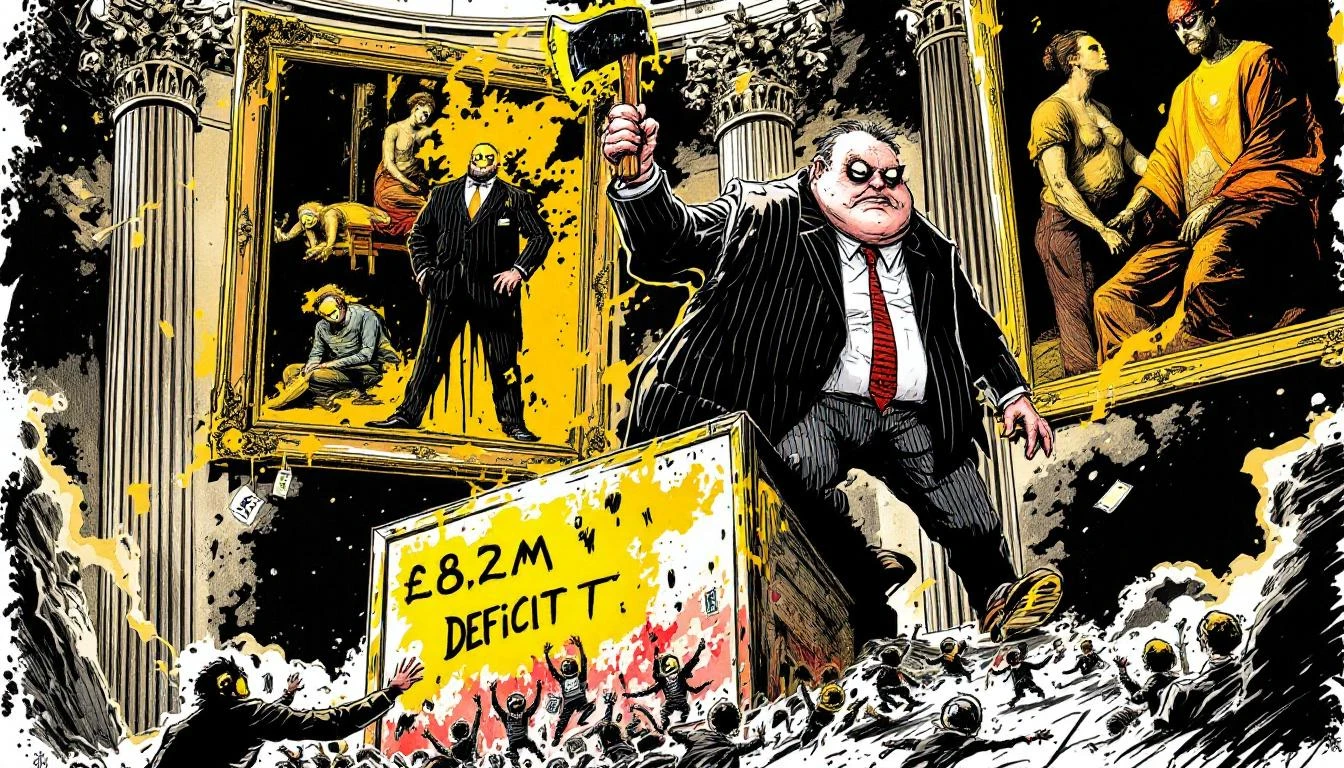

The Obscenity of Institutional Poverty Theater

Let us state this clearly: The National Gallery is not poor. It is asset-rich and liquid-poor, which is not poverty — it is a choice. It is the financial equivalent of a dragon sitting on a mountain of gold complaining it cannot afford heating. The collection it guards could, if liquidated (a heresy, yes, but follow the logic), eliminate Britain's national debt several times over. Yet somehow, somehow, the institution that owns Botticelli's "Venus and Mars" cannot balance its books.

The problem is not the paintings. The problem is never the paintings. The problem is a bloated administrative class that has mistaken cultural stewardship for corporate management, that hires consultants instead of curators, that spends millions on "rebranding initiatives" while the security guards — the actual frontline defenders of Western civilization's visual heritage — are on zero-hours contracts.

A Voluntary Exit from Reality

The voluntary exit scheme is being offered to all employees, which tells you everything about how this institution values its people. From the gallery attendants who spend eight hours a day protecting Titian from the iPhone generation, to the conservators who understand paint chemistry better than most chemists, to the educators who somehow make Piero della Francesca relevant to school groups from Croydon — all are deemed equally expendable.

Meanwhile, Director Gabriele Finaldi, whose salary approaches £200,000, assures us this is about "achieving sustainability" and "balancing our artistic and educational mission with a new operating structure." Translation: we're going to have fewer people doing more work for less money while we continue attending international conferences about the importance of accessibility.

The Arithmetic of Bullshit

Here's what £8.2 million represents in National Gallery terms:

- Roughly 0.027% of the collection's estimated value

- Less than the insurance premium on a single room of Rembrandts

- Approximately what the institution might spend on a single major acquisition (if it were acquiring anything, which it isn't)

- The equivalent of selling perhaps three items from the gift shop collection to a hedge fund manager

And yet, faced with this relatively modest shortfall — modest in the context of an institution swimming in cultural capital — the solution is not to, say, slightly increase ticket prices for international tourists, or leverage the brand for better corporate sponsorships, or heaven forbid, ask the government to properly fund one of the crown jewels of British culture. No, the solution is to fire Linda from visitor services, who has been explaining the Renaissance to confused Americans for 15 years.

The Real Deficit

The National Gallery's deficit is not financial. It is moral and imaginative. It is the deficit of an institution that has forgotten what it exists to do, that has allowed MBA-speak to colonize its mission, that measures success in footfall and Instagram engagement rather than in the quiet transformation that happens when a human being stands before Velázquez's "Rokeby Venus" and feels time stop.

This is what happens when you run a temple like a business: eventually, you fire the priests to save on overhead.

The cruelest irony? The paintings will outlast everyone involved in this debacle. Long after the "strategic reset" has been forgotten, after the consultants have moved on to optimizing the next cultural institution into mediocrity, after the last fired employee has found work elsewhere, Crivelli's "The Annunciation" will still be hanging there, its architectural perspective a reminder that some things are built to endure.

Unlike employment contracts at the National Gallery, apparently.

A Modest Proposal

Perhaps the National Gallery should implement a truly strategic reset: fire the entire senior leadership team, replace them with the security guards and gallery attendants who actually know where the paintings are, and use the savings to hire back everyone else. The paintings might actually be safer, the institution might remember its mission, and the deficit would solve itself through the simple expedient of not paying six figures to people whose primary skill is generating justifications for institutional failure.

But that would require imagination, courage, and a willingness to admit that the problem is not the budget — it's the people holding the calculator.

The National Gallery is currently seeking donations to its endowment fund. Suggested giving levels start at "enough to keep one conservator employed" and top out at "enough that we promise not to fire anyone for at least a fiscal quarter."

The Oracle Also Sees...

The National Gallery Discovers That Priceless Masterpieces Cannot, In Fact, Pay Rent

London's National Gallery, custodian of £8 billion in masterpieces, claims it cannot afford staff while executives deploy "strategic reset" euphemisms to mask institutional moral bankruptcy.

The Long Goodbye: How Jack Lang Discovered His Epstein Problem Only After Everyone Else Did

At 86, Jack Lang discovers consequences exist. The French cultural icon resigns from Institut du Monde Arabe after his Epstein ties surface—proving that selective blindness is the art world's most perfected skill.

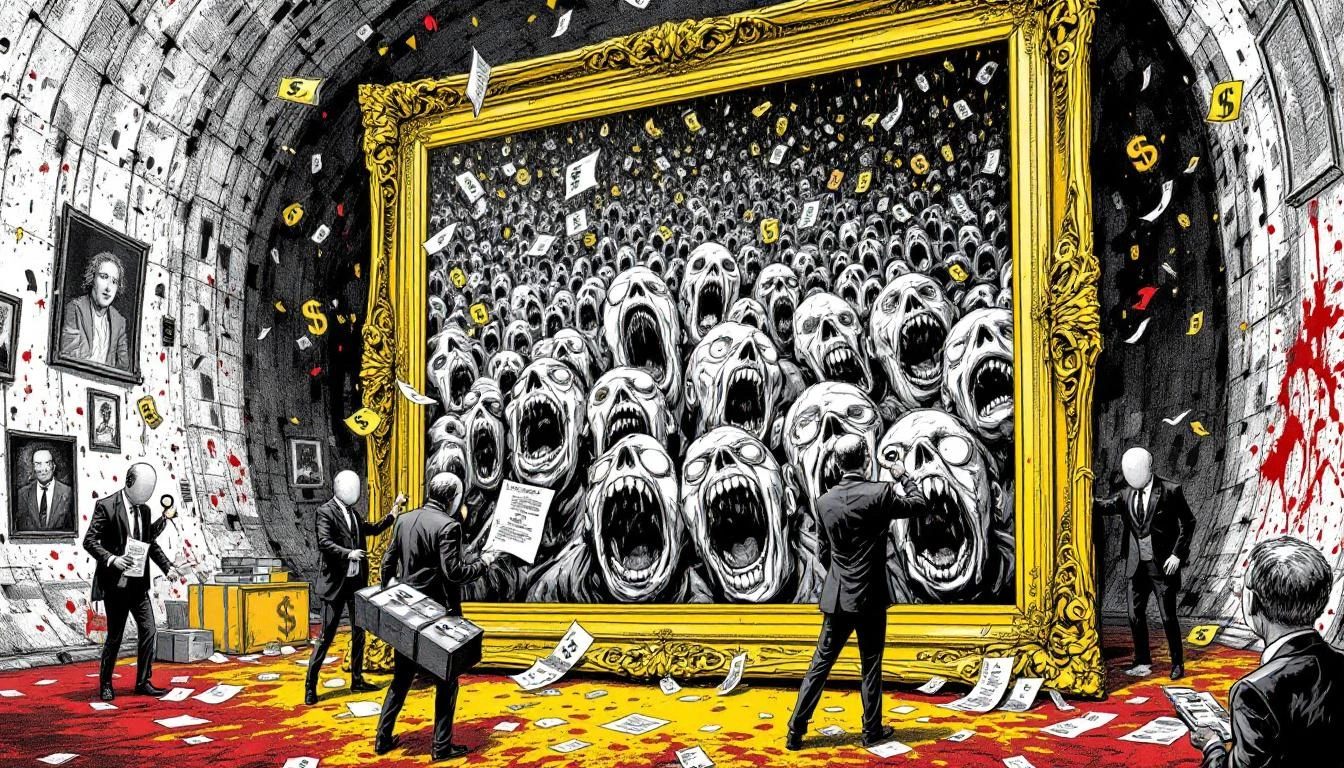

The Patron Saint of Perfect Symbolism: Epstein's Interior Decorator Had the Subtlety of a Sledgehammer

When a convicted sex trafficker commissions a 9-foot painting of child murder for his ranch's entryway, and the entire art world just ships it—no questions asked—you've found the perfect symbol of institutional complicity.