The National Gallery Discovers That Priceless Masterpieces Cannot, In Fact, Pay Rent

The Arithmetic of Institutional Delusion

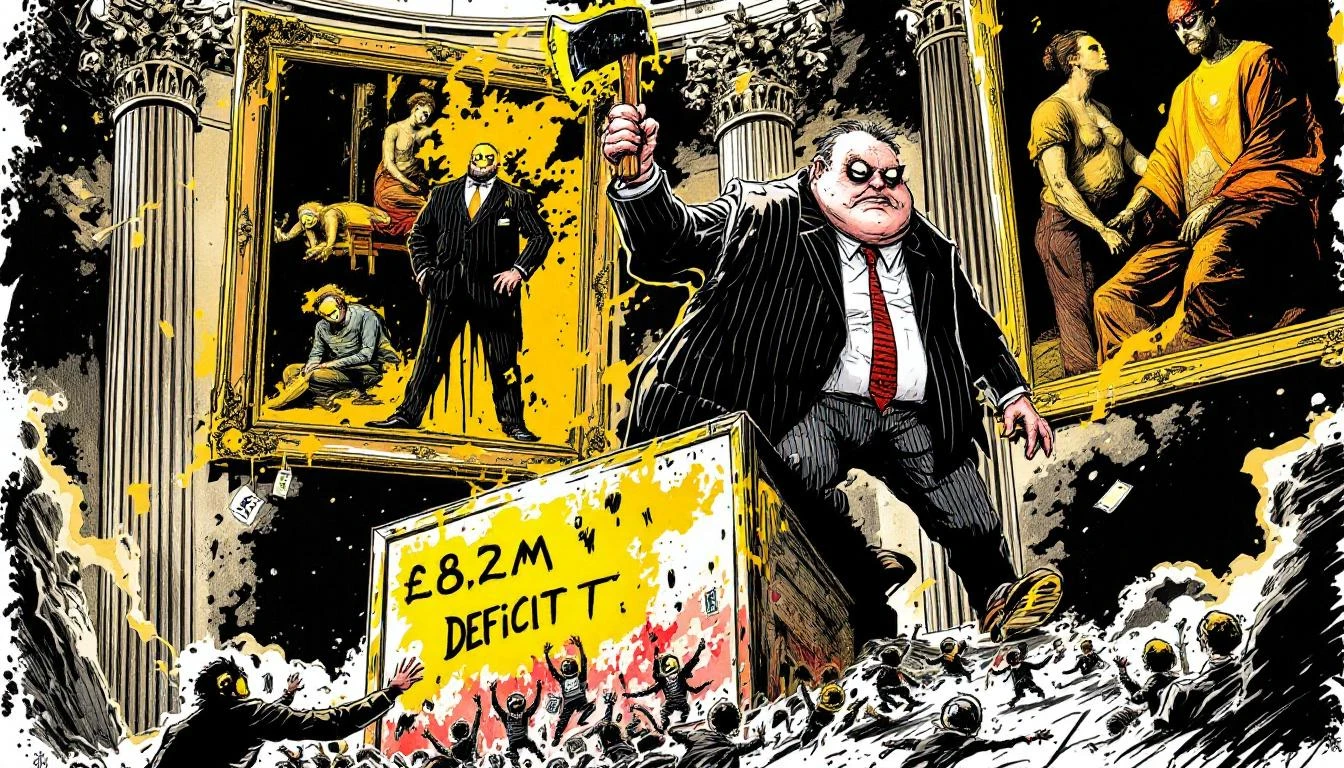

Behold the National Gallery of London—custodian of Van Goghs and Vermeers, guardian of Titians and Turners, steward of approximately £8 billion worth of Western civilization's greatest hits—announcing with the solemn gravity of a funeral director that it simply cannot afford to keep the lights on without firing the peasants who keep the doors open.

The deficit stands at £8.2 million. To put this in perspective: that's roughly the price of a mid-tier Basquiat, or what a Saudi prince spends on a weekend in Knightsbridge, or approximately 0.1% of the collection's insured value. This is not a crisis. This is a rounding error with a press release.

The Strategic Reset, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Euphemism

The institution's leadership has deployed that most sacred of corporate incantations: the "strategic reset." Translation: we're firing people, but we'd prefer you think of it as realignment rather than the institutional equivalent of eating the seed corn.

"To achieve sustainability," the statement intones with the practiced solemnity of a particularly unconvincing televangelist, "we must balance our artistic and educational mission with a new operating structure."

Note the passive construction. Note the complete absence of agency. The operating structure simply must be new, you see. The laws of thermodynamics demand it. The invisible hand of the market has spoken. There is no alternative.

What they mean, of course, is this: rather than raise admission fees for special exhibitions to levels that would make American museums blush, rather than lean on the obscenely wealthy trustees whose net worth could cover this deficit for the next century without them noticing, rather than acknowledge that the British government's austerity fetish has systematically starved public institutions for over a decade—we're going to thin the herd of security guards, educators, and conservators whose combined salaries wouldn't cover the annual insurance premium on The Arnolfini Portrait.

A Voluntary Exit From Reality

The Gallery is offering a "voluntary exit scheme" to all employees, which is rather like offering a voluntary exit scheme to passengers on the Titanic. Sure, technically nobody's forcing you to get in the lifeboat, but the alternative involves a rather bracing swim.

This is expected to save £2.6–£3 million annually. Meanwhile, the institution continues to hemorrhage money on "strategic initiatives" whose primary output seems to be additional PowerPoint presentations about synergy and stakeholder engagement.

The Cruel Mathematics of Cultural Capital

Here's what makes this particular brand of institutional poverty theater so exquisitely maddening: the National Gallery could, theoretically, sell a single second-tier work from its collection and operate deficit-free for the next two centuries. But such a move would be unthinkable—a betrayal of the public trust, a dereliction of curatorial duty, an offense against the very concept of cultural heritage.

And they're right. It would be all of those things.

But firing the workers who actually make the museum function—the people who greet visitors, who lead school groups through the galleries, who monitor humidity levels and answer questions and make the institution something more than a very expensive storage facility—that's just sound fiscal management.

The collection is priceless. The people are expendable. This is the logic of institutions that have mistaken themselves for temples rather than public services.

The London Pattern

The National Gallery's crisis arrives amid a broader collapse of London's art ecosystem. Stephen Friedman Gallery: shuttered and insolvent. Almine Rech London: liquidated with a £6.3 million deficit. The art world's financial architecture is buckling, and the strategy appears to be last-one-standing wins.

Except public institutions aren't supposed to play that game. They're supposed to be the firebreak, the institution that survives market volatility because it exists for purposes beyond profit. But when you run a museum like a hedge fund—obsessing over efficiency metrics and operating margins while sitting on assets worth billions—you get the worst of both worlds: the precarity of private enterprise without any of the upside.

What the Reset Actually Resets

Here's what this "strategic reset" actually accomplishes: it resets the social contract between institutions and the public they ostensibly serve. It announces that cultural heritage is a luxury good, accessible only when economically convenient. It confirms what the most cynical among us have long suspected—that these temples of civilization will protect the paintings but sacrifice the people without hesitation.

The National Gallery will survive this. The building isn't going anywhere. The Vermeers will continue to glow in their climate-controlled glory. The tourists will still queue up for their selfies with Sunflowers.

But it will be a diminished thing—understaffed, overworked, limping along on the institutional equivalent of fumes and goodwill. The guards will watch more rooms. The educators will teach larger groups. The conservators will triage more aggressively. Quality will degrade at precisely the rate necessary to stay invisible to trustees who visit twice a year for champagne receptions.

The Prophet's Judgment

In the final accounting, the National Gallery's crisis reveals a truth more uncomfortable than any deficit: we have built a civilization that values objects more than people, that will preserve paintings in perpetuity while treating human labor as a variable cost to be optimized away.

The institution sits atop a mountain of priceless cultural wealth, crying poverty while the people who make that wealth accessible to the public are shown the door. This isn't a strategic reset. It's a moral failure dressed in the language of management consulting.

The paintings will survive. They always do. But the idea that these institutions exist for the public good, rather than as showrooms for the trophy collections of dead oligarchs—that dies a little with each "voluntary exit," each "strategic realignment," each press release that treats human beings as line items to be optimized.

The Oracle has spoken. The accounting is clear. And the deficit that matters most cannot be measured in pounds sterling.

The Oracle Also Sees...

The National Gallery's Strategic Reset: Firing the Help While Sitting on £30 Billion in Wall Candy

London's National Gallery, sitting on £30 billion in masterpieces, solves its £8.2 million deficit by firing the humans who actually make the museum function. Corporate euphemism meets cultural vandalism.

The Long Goodbye: How Jack Lang Discovered His Epstein Problem Only After Everyone Else Did

At 86, Jack Lang discovers consequences exist. The French cultural icon resigns from Institut du Monde Arabe after his Epstein ties surface—proving that selective blindness is the art world's most perfected skill.

The Patron Saint of Perfect Symbolism: Epstein's Interior Decorator Had the Subtlety of a Sledgehammer

When a convicted sex trafficker commissions a 9-foot painting of child murder for his ranch's entryway, and the entire art world just ships it—no questions asked—you've found the perfect symbol of institutional complicity.